by Denise Silva (text and images)

Denise.Silva@aicpa-cima.com

The Aurora Borealis is often referred to as the Northern Lights because we see it to our north. But this is a bit of a misnomer, as the “lights” are also seen in the Southern Hemisphere, where they are referred to as the Aurora Australis. In fact, not only does Earth have auroral displays, but auroras can be seen on images of other celestial bodies, such as Jupiter, Saturn and Mars.

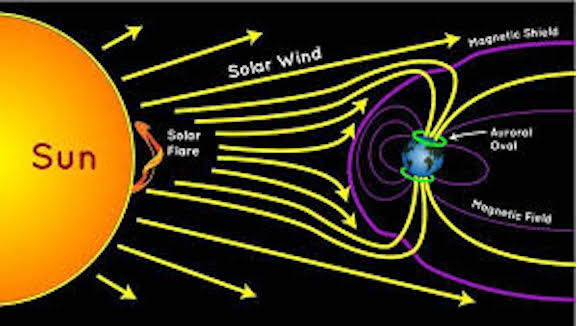

In the 1600s, Galileo coined the term “aurora borealis” after Aurora, the Roman goddess of morning or dawn and Boreas, the Greek god of the north wind. According to NASA, the oldest recorded citing of the aurora was in 2600 B.C. in China. Auroras are caused by the collision of particles released from the sun (solar wind or coronal mass ejections) resulting in the excitation of gases (oxygen and nitrogen) in Earth’s atmosphere. These excitations release photons of light at different wavelengths, resulting in auroral displays. These displays appear as ribbons, shafts, curtains, or bands of colored light in the night sky. Although auroras happen all year long, both during the day and at night, they are only visible in the night sky, most often between the months of September and April, when the sky is at its darkest for the longest periods.

This phenomenon happens when a coronal mass ejection or solar wind is emitted from the sun in the direction of Earth. The emitted particles move through space, coming into contact with Earth’s magnetic shield, initially elongating it and pushing it out of shape. When the atmosphere snaps back into is circular shape, the particles are deposited at the northern and southern poles, where they move through the atmosphere in an oval. The oval then moves from east to west, until it finally dissipates. The colors of the aurora are caused when oxygen and nitrogen gases in Earth’s atmosphere are excited.

The stronger the geomagnetic storm, the further the aurora reaches into lower latitudes.

The colors of the aurora are caused when oxygen and nitrogen gases in Earth’s atmosphere are excited.

- At the highest altitudes, excited atomic oxygen emits light at 630 nm, resulting in hues of red.

- At lower altitudes, excited atomic oxygen emits light at 557 nm, resulting in green. Since at this altitude, there is a higher concentration of oxygen and generally human eyes are more sensitive to green, green is the most common color seen. At these lower altitudes, there is also the excitation of molecular nitrogen and the blending of the excited oxygen and nitrogen result in pink or yellow lights.

- At yet lower altitudes, where atomic oxygen is less common and molecular nitrogen is more prevalent, the light produced can be seen as red and blue with blue being dominant at 430 nm.

- Yellow and pink are a mix of red and green or blue. Other shades of red, as well as orange, may be seen on rare occasions; with yellow/green being the most common.

Can we see all these colors in the sky? Well, it depends. Human retinas are made of rods and cones. Rods see in shades of grey, while cones interpret light in various wavelengths of color. When in darkness, we see light and shadow and very little “color”. So, if the aurora is active but the display is not intense, the excitations may not be emitting enough “light” to activate the cones in our eyes, so we don’t see colors. When the display is intense, as was in March and most recently April 23, seeing colors is more likely. Often, we will see green first and most prominently. Seeing colors will depend on both the intensity of the display, the ambient light (moon or no moon) and each individual person’s eyesight. So how we will know if we are seeing the aurora? Look for movement of clouds or mist that doesn’t seem normal. Clouds don’t gyrate–they float through the sky. So, if you see what seems to be a “cloud” but it is moving up and down or in a wavy manner, it is quite possibly an aurora. To truly tell, grab a camera (even your cell phone) and take a picture. If the picture reveals green or any other colors, then it is an aurora. If the picture reveals whites or greys, then it’s a cloud.

Why do cameras pick up so much color, even though we don’t see it? Cameras accumulate light over time. Generally speaking, to capture a picture of the aurora, the photographer will have their camera shutter open for a few seconds (depending on the display, camera settings will need to be adjusted). In the amount of time the shutter is open, the camera’s sensor is collecting light and revealing the colors being created by the collisions between molecules as noted above.

Scientists have determined that the sun is a cycle of activity that ebbs and flows over period of years. The period tends to be an 11-year cycle, with the cycle reaching its lowest point in 2020. This means that the sun is in a period of increased activity over the next 4-5 years before starting to wane again. For us, that may mean more opportunities for viewing. In 2023, auroras reached Flathead Valley in February, March, and April. We are also moving into spring and summer when the sky doesn’t get dark until very late. So, there may be opportunities, but there will be fewer until next fall.

There are some tools that can make it easier to know a. viewing opportunity is coming. I find the best applications are My Aurora Forecast Pro (for Android and iPhone) and Space Weather Live (for Android and iPhone). Both applications provide predictions and a visual display of the aurora oval. I have noticed that even when one of these applications says the chance of seeing the aurora is low, depending on where you are you still may see it. It just may not be intense, and it will be in the sky to the far north. Space Weather also alerts users when for coronal mass ejections. This feature is very useful, because it allows for some earlier planning because once the alert happens there is time before the gases reach Earth for you to find a dark sky location!

Thank you for sharing this informative and inspiring article! The photography is amazing; I really like the local pictures – it is proof that we don’t have to drive miles away to see the aurora!