by Skip Via

skip@westvalleynaturalists.org

To take a virtual tour of the West Valley area, click here

If you have driven around western Montana, you may have the feeling that you’re always in a valley between two mountain ranges. There’s a reason for that. It’s called Basin and Range Topography.

The Flathead Valley is situated between two such ranges–the Salish Mountains to the west and the much larger Rocky Mountains (the Swan Range, Whitefish Range, and Mission Ranges) to the east. The valley runs north-south between these ranges. This particular arrangement contributes in part to the different weather patterns and microclimates that we experience in the valley. For example, moisture laden clouds that make their way over the Salish range tend to pile up against the Swans and deposit more of their moisture there. That’s why the eastern part of the valley is typically wetter than the western side.

This basin and range topography is typical of western Montana and throughout the Rocky Mountains. Valleys tend to run north-south between ranges, and the change between flatter valley lands and much steeper mountain ranges occurs fairly abruptly. We experience these changes when we drive east-west and cross mountain passes every so often. That’s due to the way this part of the world was formed.

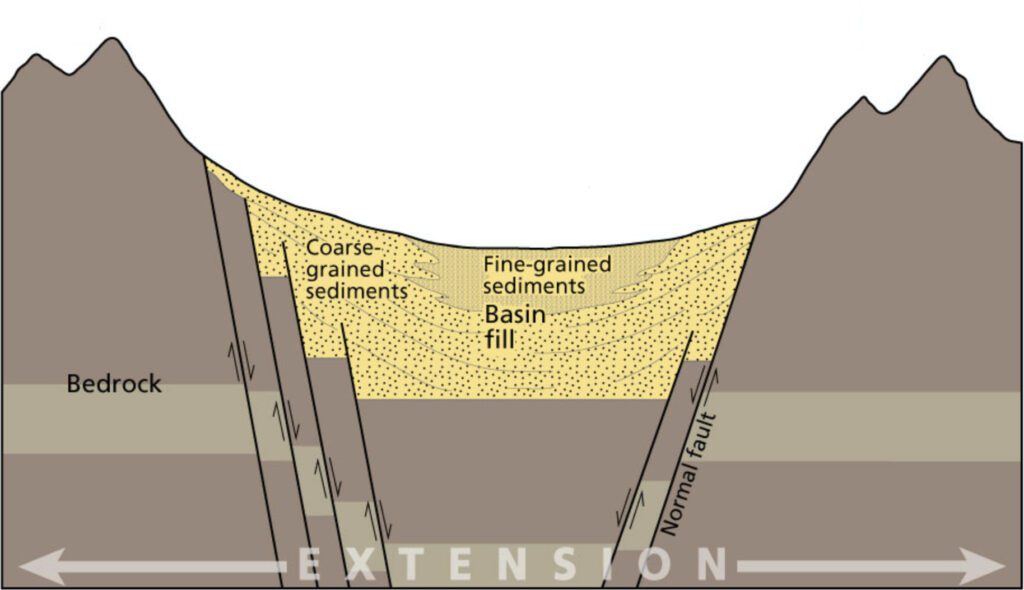

About 20 million years ago, well after the uplifting and folding that created the Rocky Mountains (and the Lewis Overthrust) occurred, the crust under this area began to stretch sideways, or east-west. That process thinned out the crust under the mountains, and it created faults–called normal faults–running north-south as a result of that stretching. In a normal fault, blocks of crust slide up or down relative to each other. The upward movement creates ranges, and the downward movement creates basins. Basins tend to fill with sediments washed down from the mountains.

In the case of western Montana, that wasn’t the most recent terraforming event. Glaciation from the Cordilleran ice sheet from the last ice age scoured the mountains and valleys to a large extent. Evidence of the scouring is clearly visible from Kalispell at the northern end of the Mission Range. The tops of the northernmost mountains of the range were sheared off by glaciation. On a clear day you can easily see where that process ended, as the the range suddenly becomes more rugged toward the south.

So next time you drive along Foothills Road next to the Swans, consider what you are looking at–the boundary between the basin of the Flathead Valley and the range of the Swan Mountains. Pretty cool.

For more information about the geological history of the Flathead Valley, visit this page by Dr. Lex Blood.